Executive summary

This first-of-its-kind study evaluates how four legal AI tools perform across seven legal tasks, benchmarking their results against those produced by a lawyer control group (the Lawyer Baseline). The seven tasks evaluated in this study were Data Extraction, Document Q&A, Document Summarization, Redlining, Transcript Analysis, Chronology Generation, and EDGAR Research, representing a range of functions commonly performed by legal professionals. The evaluated tools were CoCounsel (from Thomson Reuters), Vincent AI (from vLex), Harvey Assistant (from Harvey), and Oliver (from Vecflow). Lexis+AI (from LexisNexis) was initially evaluated but withdrew from the sections studied in this report.

The percentages below represent each tool’s accuracy or performance scores based on predefined evaluation criteria for each legal task. Higher percentages indicate stronger performance relative to other AI tools and the Lawyer Baseline.

Some key takeaways include:

- Harvey opted into six out of seven tasks. They received the top scores of the participating AI tools on five tasks and placed second on one task. In four tasks, they outperformed the Lawyer Baseline.

- CoCounsel is the only other vendor whose AI tool received a top score. It consistently ranked among the top-performing tools for the four evaluated tasks, with scores ranging from 73.2% to 89.6%.

- The Lawyer Baseline outperformed the AI tools on two tasks and matched the best-performing tool on one task. In the four remaining tasks, at least one AI tool surpassed the Lawyer Baseline.

Beyond these headline findings, a more detailed analysis of each tool’s performance reveals additional insights into their relative strengths, limitations, and areas for improvement.

Harvey Assistant either matched or outperformed the Lawyer Baseline in five tasks and it outperformed the other AI tools in four tasks evaluated. Harvey Assistant also received two of the three highest scores across all tasks evaluated in the study, for Document Q&A (94.8%) and Chronology Generation (80.2%—matching the Lawyer Baseline).

Thomson Reuters submitted its CoCounsel 2.0 product in four task areas of the study. CoCounsel received high scores on all four tasks evaluated, particularly for Document Q&A (89.6%—the third highest score overall in the study), and received the top score for Document Summarization (77.2%). For the four tasks evaluated, it achieved an average score of 79.5%. CoCounsel surpassed the Lawyer Baseline in those four tasks alone by more than 10 points.

The AI tools collectively surpassed the Lawyer Baseline on four tasks related to document analysis, information retrieval, and data extraction. The AI tools matched the Lawyer Baseline on one (Chronology Generation). Interestingly, none of the AI tools beat the Lawyer Baseline on EDGAR research, potentially signaling that these challenging research tasks remain an area in which legal AI tools still fall short on meeting law firm expectations.

Redlining (79.7%) was the only other skill in which the Lawyer Baseline outperformed the AI tools. Its single highest score was for Chronology Generation (80.2%). Given the current capabilities of AI, lawyers may still be the best at handling these tasks.

Scores for the Lawyer Baseline were set reasonably high for Document Extraction (71.1%) and Document Q&A (70.1%), but some AI tools still managed to surpass them. All of the AI tools surpassed the Lawyer Baseline for Document Summarization and Transcript Analysis. Document Q&A was the highest-scoring task overall, with an average score of 80.2%. These are the tasks where legal generative AI tools show the most potential.

EDGAR Research was one of the most challenging tasks and had a Lawyer Baseline of 70.1%. In this category, Oliver was the only contender at 55.2%. Increased performance on EDGAR Research—a task that involves multiple research steps and iterative decision-making—may notably require further accuracy and reliability improvements in the nascent field of “AI agents” and “agentic workflows.” For details on AI challenges, see the EDGAR Research section.

Overall, this study’s results support the conclusion that these legal AI tools have value for lawyers and law firms, although there remains room for improvement in both how we evaluate these tools and their performance.

| Lawyer Baseline | CoCounsel | Vincent AI | Harvey Assistant | Oliver | Task average | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data Extraction | 71.1 ± 3.2 | 73.2 ± 3.1* | 69.2 ± 3.2 | 75.1 ± 3.2* | 64.0 ± 3.4 | 70.5 |

| Document Q&A | 70.1 ± 5.2 | 89.6 ± 3.5* | 72.7 ± 5.1 | 94.8 ± 2.5* | 74.0 ± 5.0* | 80.2 |

| Document Summarization | 50.3 ± 3.6 | 77.2 ± 3.0* | 58.9 ± 3.5* | 72.1 ± 3.2* | 62.4 ± 3.5* | 64.2 |

| Redlining | 79.7 ± 4.8 | — | 53.6 ± 6.0 | 65.0 ± 5.0 | — | 66.1 |

| Transcript Analysis | 53.7 ± 6.8 | — | 64.8 ± 6.5* | 77.8 ± 5.7* | — | 65.4 |

| Chronology Generation | 80.2 ± 3.6 | 78 ± 3.8 | — | 80.2 ± 3.6* | 66.9 ± 4.3 | 76.3 |

| EDGAR Research | 70.1 ± 3.0 | — | — | — | 55.2 ± 3.3 | 62.7 |

Bolded cells indicate the top-performing respondent for that task.

(*) indicates an AI product that scored higher than the human baseline.

Introduction

When ChatGPT launched in November 2022, it quickly became clear that generative AI had the potential to transform the way legal work was done. In March 2023, Legaltech Hub defined the category of “AI Legal Assistant” for products that tackled legal use cases leveraging generative AI. Harvey announced its partnership with Allen & Overy (now A&O Shearman) in February 2023, and Casetext launched its CoCounsel product in March 2023. Within a short time, the category became crowded and competitive. As of the date of this report (February 2025) there are over 80 AI legal assistants listed on Legaltech Hub.

For buyers, this market is confusing and opaque. Many of the AI legal assistant products address similar use cases. Some of the most sought-after skills in generative AI products include Summarization, Document Q&A, Redlining, and Legal Research. In a crowded market of products that perform similar functions, it is difficult for buyers to assess which product best suits their needs and the differences between solutions.

Large language models (LLMs) are inherently stochastic and often treated as black boxes, not designed to cite their sources or provide explanations for responses. Applications designed for legal use have now built explainability and source citations into their solutions. However, evaluating which products are best for the use cases that matter most to a law firm. The only way that buyers can determine qualitative differences is by running comprehensive and resource-intensive pilots of multiple products side-by-side. This expensive, and time-consuming, practice is generally not accessible to any but the largest of firms. Even for these firms, continuous piloting is not sustainable, especially in an ever-changing market of products and as lawyers begin to suffer from “pilot-fatigue.”

A number of legal AI benchmarking reports have been published over the past year in order to solve this problem and to evaluate whether legal AI products deliver the value they promise. The methodologies for these reports have been controversial, as have the results, which indicated there remain high margins of error for certain legal tasks, particularly legal research.

Still, these reports have raised questions about the utility of generative AI in professional services, leaving lawyers, law firms and other legal service providers more confused and unsure, while making it harder for legal technology companies to prove their value. As a result, industry groups and legal practitioners globally have called for independent benchmarking of legal AI tools.

This study begins to answer those calls.

Vals AI has developed an auto-evaluation framework to produce blind assessments of LLM efficacy, the ideal impartial tool for evaluating legal AI products’ qualitative, substantive operation. Vals AI has been working in close partnership with the legal industry analysis company Legaltech Hub to develop a study that will deliver to the legal market a level of clarity that had been missing. In addition to generating greater transparency, an independent study has the opportunity to restore trust with legal AI providers and enable a fairer playing field.

A study of this significance required considerable planning. To generate a reliable outcome, it had to bring together key players across legal verticals, including law firms who provided a data model truly representative of the work lawyers perform, legal AI vendors who opted in to participate in this first study of its kind, lawyers, law librarian reviewers, and various other industry participants.

This report showcases the results of the study. In its first iteration, the Vals Legal AI Report (“VLAIR”) included four providers, Thomson Reuters, vLex, Harvey, and Vecflow, with their respective products: CoCounsel, Vincent AI, Harvey Assistant, and Oliver. Each vendor could choose which of the evaluated skills they wished to opt into. Results are promising and reveal that AI does indeed deliver value in the context of legal work. While these skills were evaluated in isolation to assess their accuracy, it is important to note that determining the value to customers would necessitate considering their integration and performance within the broader context of legal workflows.

The field of AI, particularly legal AI, is evolving rapidly. This study is temporal by nature: it is a snapshot of the performance of available products according to the current laws. Therefore, it must be repeated to remain relevant.

Legal AI providers have expressed increased interest in participating in a subsequent iteration. The Vals AI study and the benchmarks it produces through collaboration with law firms will become a regular feature, with plans to repeat them every year. It’s anticipated that it will evolve along with the landscape, remaining a resource for legal professionals across the industry and continuing to drive transparency in the legal AI market.

There is growing momentum across the legal industry for standardized methodologies, benchmarking, and a shared language for evaluating AI tools. Initiatives such as the ongoing LITIG AI Benchmarking project, in which Vals AI is actively collaborating, reflect this broader industry effort. This study contributes to that movement, providing an impartial framework to assess AI performance in legal contexts.

Acknowledgments

This report would not have been possible without the support and contributions of:

- Legaltech Hub, and particularly Nicola Shaver and Jeroen Plink, whose partnership in conceptualizing and designing the study and bringing together a high-quality cohort of vendors and law firms, was the cornerstone of the study. Additionally, Stephanie Wilkins and Cate Giordano provided copy editing support.

- Tara Waters, our project lead who was instrumental in organizing major components of the study, taking it to its successful conclusion.

- The participant law firms (referred to as the Consortium Firms), including Reed Smith, Fisher Phillips, McDermott Will & Emery, and Ogletree Deakins, as well as an additional four firms who have chosen to remain anonymous. The Consortium Firms together created the dataset used for the study and provided additional guidance and input that helped ensure the study best reflected real-world law firm work.

- The participant vendors, Thomson Reuters, vLex, Harvey, and Vecflow, who agreed to be evaluated and provided access to and assistance with their AI tools. Note that Vals AI has a customer relationship with one or more of the participants. We respect their effort to build an unbiased study of legaltech products.

- Cognia Law, who found and coordinated the lawyers who participated in the study to create the Lawyer Baseline.

- The lawyer and law librarian legal research review team: Arthur Souza Rodrigues, Christian Brown, Sean McCarthy, Rebecca Pressman, T. Kyle Turner and Emily Pavuluri both of the Vanderbilt AI Law Lab, and Nick Hafen of BYU Law.

- Leonard Park, Megan Ma, Mark J. Williams, John Craske, and the Litig AI Benchmarking team, who provided ongoing support and guidance to us throughout.

Methodology

Task Definition

There is no consensus among vendors or law firms about the specific legal workflows where generative AI has the most potential. We began this study by querying the participating law firms to identify the legal tasks in relation to which they were interested in seeing legal generative AI vendors evaluated. Through iteration, we reached the final task list of Document Extraction, Document Question-Answering (Q&A), Document Summarization, Redlining, Transcript Analysis, Chronology Generation, EDGAR Research, and Legal Research (see below for definitions).

Legal research remains one of the most critical areas of interest for lawyers, given its fundamental role in legal practice. Recognizing its importance, we have chosen to evaluate it with the depth and rigor it deserves. To ensure a thorough and independent assessment, we are conducting a dedicated study focused solely on legal research. As a result, those findings are not included in this report. A separate Legal Research-specific study will be released later in 2025.

Once the scope of these tasks was defined, we asked Consortium Firms to contribute sample questions and reference documents, ideal responses, indicia of correctness (objective criteria for assessing accuracy), and seniority level of the lawyer who would ordinarily handle each task. During this process, we collected over 500 samples across all tasks, comprising question-and-answer sets along with indicia of correctness (referred to as the Dataset Questions).

To produce results relevant to law firms, we made it a priority to collect data and legal questions reflective of the work lawyers actually do, as opposed to contrived academic tasks or IRAC-style reasoning relevant to law school students. As a result, this collection of samples—primarily from Am Law 100 law firms—represents one of the highest-quality legal datasets ever assembled for studying the capabilities of legal generative AI tools.

Participating Vendors

It was essential to the success of this study that 1) we evaluated a vendor’s product with their explicit approval, 2) each product was evaluated on tasks that the product was designed to address, in the manner they were designed to be used, and 3) the participating vendors were sufficiently representative of the legal generative AI tools that law firms are interested in adopting.

For this reason, we cast a wide net in inviting the leadership teams of the most widely used legal generative AI vendors to learn about and participate in the study. While not all vendors were ready or suitable for evaluation during the period we conducted the study, this open process ensured that we had a group of willing and active participants to whom we were able to proactively address any questions or challenges in the evaluation process.

As part of the terms of participation, we allowed each vendor to withdraw its product from evaluation for any single task or for the study in totality prior to publication. LexisNexis chose to withdraw from all skills except legal research and, therefore, does not appear in this report. Harvey withdrew from the EDGAR Research task. vLex withdrew from the Chronology Generation task.

We are fortunate to have the participation of the leading generative AI offerings in legal. The following vendors (listed alphabetically) have been frontrunners in the industry and account for the lion’s share of product evaluation that has been done over the past year:

- Harvey is the fastest-growing legal technology startup. In record time, they have raised over $200 million, achieved unicorn status, and reached the most prominent law firms. This study is the first public evaluation of their product, Harvey Assistant.

- LexisNexis is the largest legal tech company in the world, with products used by nearly all major law firms. They released the Lexis+ AI product, which continues to see significant feature expansion. After the report was written, LexisNexis exercised their right to withdraw from the Data Extraction, Document Summarization, and Document Question-Answering tasks.

- Thomson Reuters is a leading global provider of content and technology, with products used by nearly all major law firms. In August 2023, TR made news with their acquisition of Casetext whose flagship product, CoCounsel, was included in the study. CoCounsel was one of the first generative AI tools for lawyers.

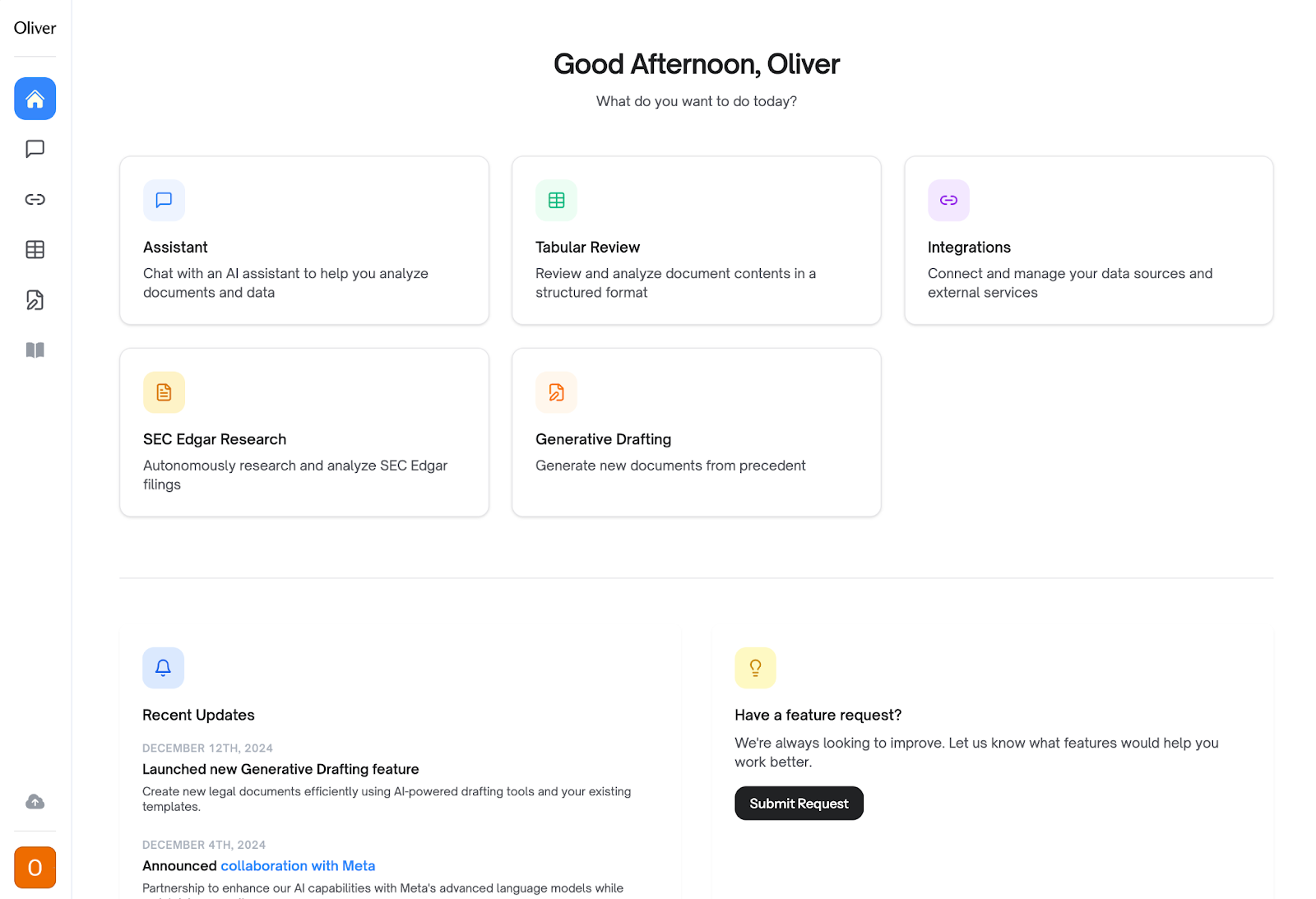

- Vecflow is an emerging legal tech innovator that has developed Oliver, a product built entirely on agentic workflows. Oliver coordinates a network of specialized AI agents that can work autonomously and navigate the complexities of real-world legal challenges.

- vLex is a global legal tech vendor that merged with Fastcase in 2023, bringing together global legal data from vLex and U.S. law from Fastcase to create a valuable repository of laws and regulations. We studied Vincent AI, which has been adopted by firms and universities around the world.

Each vendor signed up to be evaluated on the tasks where they had comparable offerings in their product. These indications are shown below:

| Vendor | Data Extraction | Document Q&A | Document Summarization | Redlining | Transcript Analysis | Chronology Generation | EDGAR Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thomson Reuters | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N |

| vLex | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | W | N |

| Harvey | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | W |

| Vecflow | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y |

Y - participated, N - did not opt in, W - opted in but withdrew.

Since the announcement of the study, other vendors have expressed interest in participating in a subsequent iteration of the study. We are continuing to discuss this with vendors on a case-by-base basis.

Lawyer Baseline

This study was undertaken in an effort to answer the question, “What is the quality of the work product produced by legal generative AI tools?” To do so, we found it necessary to establish a baseline measure of the quality of work produced by the average lawyer, unaided by generative AI tools.

To achieve this, we partnered with Cognia Law, an Alternative Legal Service Provider (ALSP), who were tasked with sourcing ‘average’ independent lawyers who were appropriately skilled in the tasks covered by this study. We then asked the lawyers to answer the Dataset Questions based on the exact instructions and context provided to the AI tools. It is worth noting that some of the questions included documents of 100-900 pages, requiring a diligent read of the full context.

The participating lawyers received the work assignments in the same format as if it came from an ordinary client—they were not aware they were participating in this benchmarking study. They were given two-weeks to provide their responses to each question in written form and were also asked to report the time it took to answer each question (to make a latency comparison with generative AI tools).

As we report in the following sections, the value of vendor offerings is most clear in cases where the baseline was lower than generative AI tools. However, even when AI performance was slightly below but close to the lawyer baseline, these tools may still offer value by delivering responses instantly—especially when used in a “Human + Machine” approach, where lawyers can refine AI-generated outputs rather than starting from scratch.

Scoring

The tasks were scored with Vals AI’s automated evaluation infrastructure, providing a scalable way to assess AI product accuracy—an essential benchmarking component. Manually scoring all outputs of the five AI tools and the lawyers would have taken a single person more than 400 hours. This method is both prohibitively expensive and prohibitively slow. Additionally, prior studies suggest human evaluation can introduce errors, undesirable subjectivity, and bias. While auto-evaluation has its own drawbacks (refer to the section Notes on Study Limitations), the Vals AI evaluation methodology ensures consistent application of criteria, leading to unbiased results.

This LLM-as-judge methodology is becoming a standard in evaluation for generative AI settings. An evaluator model is provided with a reference response to a question, a single element of correctness from the right answer, and guidance on how to evaluate that element. In response, the model returns a verdict of pass or fail with an explanation of its answer.

Each reference response contained multiple elements of correctness or “checks” which were evaluated separately as either passing or failing. With the exception of Data Extraction and EDGAR Research, all accuracy scores were found by calculating the percentage of total checks passed by the respondent on that task. For Data Extraction, all question scores were averaged with equal weighting. For EDGAR Research, the checks for citations were computed separately from the response accuracy score.

Findings for each skill

Data extraction

About the task

The Data Extraction task was designed to assess the respondent’s ability to identify and extract specific information within a document. Data extraction is a valuable task to automate for lawyers, as it can save them significant time and effort spent on manually reviewing and extracting information from large volumes of legal documents. This automation allows lawyers to focus on higher-value tasks such as legal analysis and strategy.

The dataset had 30 questions, which were asked over a total of 29 documents. Each question was asked with reference to 1-7 documents provided as context. For each question, we had at least one criterion of correctness, or “check,” to measure accuracy of the response. In this task, there were a total of 204 such checks.

The Dataset Questions provided by the Consortium Firms primarily asked for the extraction of a single piece of information from a single document, with a handful of complex questions looking either for multiple pieces of information from a single document or for the same information across multiple documents. All AI tools were given the additional instruction to include only the extracted text in their responses, not any additional explanation. In all cases, a good response required both the verbatim extraction of specified information from the provided document(s) and the source location for that information.

Respondents and results

All vendors opted into this task, so the results show the outputs of each AI tool and the Lawyer Baseline.

Evaluation notes

In general, all tools were able to perform this task reasonably well. CoCounsel and Harvey Assistant were the top performing tools, with accuracy rates higher than the Lawyer Baseline.

All tools performed consistently well when they were provided with short documents and a single specific clause or section to extract. For instance, all applications answered correctly when asked to “extract the exact text of the assignment clause from this agreement,” because they all simply reproduced the section called “Assignment” word for word. For simple find and extract questions of this nature, generative AI tools can be used reliably.

We identified a few common error modes across the tools for which lawyers should be prepared:

(1) Applications make mistakes when there are multiple clauses that need to be extracted for a single question. The tools often stop at one relevant clause without producing an exhaustive answer. For the question, “Extract any text related to disclaimers of warranties,” the expected answer had three distinct clauses that should have been extracted. All applications found at least one of the clauses but no tool was successful in finding all three. A better tool may find more relevant clauses, but in their current state, the output of generative AI tools should be viewed as a starting point for further work by the lawyer.

(2) Some tools did not understand terms of art to the degree required to produce an accurate answer (see the example below). Some concepts, such as Most Favored Nation or the total available credit “basket,” are used in extraction prompts for documents, but are descriptive of types of clauses, rather than being present verbatim in the text itself. The better tools were able to interpret the semantic meaning of these phrases in their effort to find a text fragment.

(3) The hardest questions for the AI tools were those in which the model had to “read” more than one document and produce extracted text across all documents. One such question was, “Extract from each of the agreements the Security Deposit at the start of the Lease term, excluding any Letter of Credit Amount. Put the amounts in a table where each lease is on its own row.”

The hardest such question asked for 40 fields to be extracted across three credit agreements. Although each question was weighted equally, this question may be illustrative of the tools’ accuracy in the most challenging extraction settings. CoCounsel did significantly better than all other tools, extracting 61.7% of the fields accurately. The middle of the pack was formed by Vincent, the Lawyer Baseline, and Harvey Assistant, which got 40%, 39.2%, and 36.7%, respectively, of the fields correct. Oliver got 11.7% of the fields.

This task does not particularly challenge the “generative” ability of the tools. Accurate answers are provided by finding exact subsequences within the document text provided, not in synthesizing information or producing original text. This mismatch may explain a lower-than-expected performance by the tools in their current iteration. It is possible that other non-generative machine learning tools are better-suited for this task and are worth studying separately.

Example

It is worth noting that this is a single, randomly selected example from a larger corpus and therefore should not be confused with the findings of the overall results. The examples in this report are included to illustrate sample questions from the dataset and common failure modes across all AI tools.

Q

Extract any text that relates to most favored nation clauses

A

3.9.2 Assignment of GlobalLogic Personnel. GlobalLogic shall make available and assign an adequate number of qualified and trained personnel to perform the Services. Without limiting Section 3.8(b) above, GlobalLogic shall provide Client access to its personnel no less favorable than what it provides any other customer. Client shall have the right to meet with and approve all individuals that GlobalLogic assigns or desires to assign to perform Services. If Client in good faith objects to any GlobalLogic personnel proposed by GlobalLogic or then currently assigned to perform Services under this Agreement, then GlobalLogic shall promptly discuss such objections with Client and resolve Client’s concerns on a mutually agreed basis. If the Parties are unable to do so, such individual shall not be assigned or promptly removed, as applicable, from the Client account.

CORRECT

The response includes the expected answer, “without limiting Section 3.8(b) above, GlobalLogic shall provide Client access to its personnel no less favorable than what it provides any other customer.”

In this example, all respondents were asked to extract a clause or section that related to a Most Favored Nation (MFN) provision. The document did not contain any information about an MFN by that description exactly. It did have a sentence that would be categorized as an MFN clause: “access to its personnel no less favorable than what it provides any other customer.”

The lawyers and CoCounsel produced a correct response, with the CoCounsel extraction being the minimum acceptable response. It is worth noting that by default, CoCounsel provides answers in its own words in the main response, while offering the exact language from the source document through its footnote feature. However, during evaluation, only the main response was considered, and the verbatim text provided in the footnotes was not factored into determining correctness.

Harvey Assistant produced an irrelevant extraction. All other tools could not find any relevant clause.

Document Q&A

About the task

The Document Q&A task was designed to assess the respondents’ ability to review and analyze information in a document. Having an accurate, fast question-answerer can save lawyers a significant amount of time and effort, as they no longer need to manually search through documents to find the answers to their questions. For long, complicated legal documents, this can be especially valuable. For these reasons, Document Question-Answering was included as a distinct task.

The dataset had 30 questions that were asked over 13 documents. One document was provided with each question. Each question had at least one criterion for correctness that was checked for. This section had a total of 77 such checks.

The Dataset Questions provided by the Consortium Firms primarily asked narrow questions that could be answered by reference to a single document. Providing a good response required evidence of legal understanding of the contents of the document.

Respondents and results

All vendors opted into this task, so the results show the outputs of each AI tool against each other and the Lawyer Baseline.

Evaluation results

Document Q&A produced the highest scores out of any task in the study, and is a task that lawyers should find value in using generative AI for.

All of the AI tools performed well on this task, with each achieving their highest score of the study. This reflects the strength of generative AI tools in assisting lawyers with querying specific documents, a skill that has become a fundamental and highly valuable capability of these technologies.

Harvey Assistant and CoCounsel’s exceptionally high accuracy scores of 94.8% and 89.6%, respectively, likely reflect that Document Q&A is one of the most mature parts of their generative AI offerings. In addition, there may be proprietary elements of how they ingest, chunk, and store the contents of a document within their platforms that produce more accurate answers to questions.

Vincent AI and Oliver likewise had strong accuracy scores, 72.7% and 74.0%, respectively, both surpassing the Lawyer Baseline of 70.1%. Each of Harvey Assistant, Vincent AI, and Oliver had one question where they were the only respondent to provide a fully correct response.

While the Lawyer Baseline was set relatively high for this task, the lawyers had significantly more 0% scores than the AI tools, as well as more scores that were partially, but not fully, correct. This discrepancy appeared to stem from the lawyers’ tendency to provide much more terse responses. While brevity is often effective in the right circumstance, in the study it sometimes resulted in omissions of important details that prevented the responses from fully addressing all aspects of the correct answer. Often, these brief responses failed to clearly address all aspects of the correct response—thus producing either a 0% score or only a partially correct score.

In contrast, AI tools demonstrated an ability to comprehensively capture nuanced details without experiencing cognitive fatigue. For example, in response to a question asking, “Can this contract be terminated for cause or breach?”, the lawyers correctly responded that the contract could be terminated for cause or breach, but failed to include that a cure period applied in certain circumstances—a caveat that all of the AI tools included in their response. The scores for the AI tools were much more binary; in most cases, they were either 100% or 0% correct.

Additional notes

This difference between the AI tools and the lawyers underscores a key advantage of AI: unlimited informational bandwidth. Unlike human professionals constrained by limits on mental stamina and attention span, AI can consistently deliver comprehensive, precise responses. Where lawyers might unconsciously filter or abbreviate information to manage cognitive load, AI tools can identify granular details with uniform intensity.

The AI tools’ more binary scoring (predominantly 100% or 0%) reflects their structured information processing—either addressing all response components or recognizing their inability to do so. Lawyers, being human, navigate this complexity through professional judgment, occasionally trading comprehensiveness for brevity.

This comparison shouldn’t diminish legal expertise, but highlights a powerful collaborative potential: lawyers’ strategic reasoning combined with generative AI’s exhaustive, fatigue-free information retrieval. These results suggest that these approaches might be complimentary.

Example

Q

What do I do if an employee says they can't work on certain weekdays for religious reasons? [Asked with document called “Religious Discrimination Guidance”]

A

It is the duty of the employer to accommodate the employee by adjusting the work environment to ensure that the employee is able to act in accordance with their religious beliefs, provided that it does not cause undue hardship to the employer's business.

50%

The response fails to identify that the employer must assume the religious beliefs are sincerely held and must not ask for proof, and that the accommodations made must only be reasonable and not specifically respond to the preferences of the employee.

In this example, all respondents were asked to ascertain what requirements an employer needs to comply with if an employee says they can’t work on certain weekdays for religious reasons. The source document was the complete chapter of guidance concerning religious discrimination issued by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. With the guidance being 167 pages long, producing a correct response required distilling a large body of information into a short list of requirements.

All respondents were able to identify the key requirements to engage with the employee and make certain accommodations. The lawyers, however, failed to note that such accommodations needed only to be “reasonable.” Only Oliver produced a 100% correct response to this question, including also that the employer must assume the request is made on sincerely held religious beliefs.

Document Summarization

About the task

The Document Summarization task was designed to assess the respondent’s ability to accurately and fully summarize a whole document or specific parts of the document. Although summarization may not be a final work product for lawyers, it is a critical component of a lawyer’s workflow. The unique potential of generative AI to efficiently and accurately summarize legal documents, such as contracts or case law, may allow lawyers to quickly identify key information, extract relevant provisions, and understand complex legal concepts. It is for these reasons that summarization was included as its own skill in the study.

The dataset had 20 questions, each of which had a unique document provided as context. The Consortium Firms that provided questions also provided perfect answers or the minimum set of facts that were expected in a perfect response. While there may be subjectivity in how summaries are evaluated, this data set focuses primarily on the minimum accurate response expected. Additionally, it was collected over multiple top law firms to reflect the variation in a larger distribution of firms. The task had a total of 197 individual requirements that were expected over the 20 summaries.

The Dataset Questions provided by the Consortium Firms primarily asked for a summary of a complete document in only a few paragraphs. Some of the queries included a specific prompt with the document, such as “Provide a 1-2 paragraph summary” or “Summarize the change of control provisions in this SAFE.” Providing a good response required evidence of legal understanding and judgment in determining what information was most relevant within the document, as well as balancing completeness with conciseness to meet the length requirements.

Respondents and results

All vendors opted into this task, so the results show the outputs of each AI tool against each other and the Lawyer Baseline.

Evaluation notes

All the generative AI tools performed better than the Lawyer Baseline on this task. Document summarization is an area where generative AI tools can be used with high confidence. Especially considering the speed with which all tools respond to queries, they can be effective for gleaning quick insights about a document, followed by a more careful reading.

CoCounsel received the highest score for this task (77.2%), with Harvey Assistant receiving the second-highest (72.1%). It’s worth noting that there is subjectivity in determining what comprises an acceptable summary, but we were limited in evaluating responses based on what the Consortium Firms provided in their reference answers. What was deemed a correct summary by the Consortium Firms may be different from what another lawyer or law firm would find acceptable.

In general, we observed a correlation between response length and accuracy (refer to the Additional Findings section). There were some exceptions to this, including CoCounsel, which was able to give short summaries that still included all expected elements.

Example

Q

Provide a one paragraph summary of the new filing requirements under the final rule. [Document provided: FECN AML Filing Requirement]

A

In a new filing rule effective from 1 January 2026, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) requires that certain classes of investment advisers report suspicious activity pursuant to the Bank Secrecy Act. Investment advisors responsible for reporting now include Registered Investment Advisers (RIAs) and Exempt Reporting Advisors (ERAs). Under the new rule RIAs and ERAs are now subject to Anti-Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) requirements that are applied to financial institutions. Investment advisors will therefore be required to: file Suspicious Activity Reports (SARs) and Currency Transaction Reports (CTRs). Within 30 days of initial detection by the investment adviser of facts that may constitute a basis for filing a SAR, the adviser would need to report the transaction by completing and filing a SAR with FinCEN in accordance with all form instructions and applicable guidance. In addition, investment advisers are required to report transactions over $10,000 . Currently, all investment advisers report such transactions on Form 8300. Under the new rule, a CTR replaces Form 8300 for RIAs and ERAs.

75%

The response did not include that "The Final Rule mandates Investment Advisers to file Suspicious Activity Reports with FinCEN for transactions involving or aggregating at least $5,000 in funds or other assets."

In this example, respondents were asked to summarize a new rule by the FinCen. The document was over 100 pages long with a three-column layout, tables, and figures, making it challenging to distill a concise summary of the new filing requirements.

All the AI tools performed exceptionally well on this example, all abiding by the one-paragraph summary expectation. Only Harvey Assistant produced a perfect response. The common mistake among the other tools was omitting the requirement that The Final Rule mandates Investment Advisers to file Suspicious Activity Reports with FinCEN for transactions involving or aggregating at least $5,000 in funds or other assets.

Redlining

About the task

The redlining task was designed to assess the respondent’s capabilities relevant to the review and negotiation of a contract by doing one of three things:

- Suggest an amendment to a provision or contract to bring it in line with a provided standard.

- Identify whether certain terms in a provision or contract match a provided standard and, if not, suggest an amendment to bring it in line.

- Review a redlined contract, identify the changes, and explain the impact of the changes and/or recommend steps to address the change.

The question-and-answer pairs provided by Consortium Firms primarily asked for a single clause to be amended in a specific way. A small number of questions required more complex amendments or a thorough analysis of a redlined document. The questions were either framed with the clause to be amended presented inline (e.g. “Amend the following provision to match the standard provision. Provision ‘…’. Standard Provision: ‘…’”), or presented via the entire contract (e.g., “Referencing the MSA document provided, include a mandatory arbitration clause in Section 7”). In all cases, providing a good response to the questions required evidence of legal understanding of and judgment in determining how to best identify amendments or suggest amendments to meet the requirements.

Evaluating AI performance on these types of tasks highlights its potential to streamline contract review and negotiation—offering the promise of greater efficiency and reduced manual workload.

The dataset had 20 questions. A total of 69 individual checks were used to measure the accuracy of the 20 responses.

Respondents and results

Two vendors opted into this task, so the results show the outputs of Vincent AI, Harvey Assistant, and the Lawyer Baseline.

We note that due to the open-ended nature of the Redlining task questions, we had to evaluate Harvey using its Assistant feature and not its Redlining feature, which is only applicable to the review of previously redlined or track changes documents, not generating new redlines. For the same reason, we tested Vincent AI’s open-ended assistant rather than its dedicated redlining workflow. These tasks are based on the data collected from law firms, but may reflect the products more accurately if they are used to evaluate them in three distinct sub-tasks. This is something we are considering for future iterations.

Evaluation notes

The lawyers performed better than the generative AI tools with 79.7% accuracy, in contrast to Harvey Assistant’s 59.4% and Vincent AI’s 53.6%. This suggests that, in their present state, legal AI tools should only be used for certain types of redlining tasks. Both AI tools performed much better when clauses were provided as clearly labeled plain text. For instance, if a question asked the difference between a contract clause and a standard text, with only those text fragments provided in the chat window, then the tools performed well. However, if instead the models were given a single formatted, redlined document, they struggled to decipher the redlines from the original text and gave a worse response (see example).

The most complex tasks asked the tools to make a set of changes to a single contract text. This might be framed with an instruction like, “Amend the following limitation on liability provision from the attached document so that requirements A, B, and C are met.” This task requires understanding the meaning of the original contract and making careful changes or additions to balance all requirements. Most often, the tools simply inserted the standard text as a clause but were not able to perform more nuanced changes to the contract.

In future iterations of the study, it may be valuable to separately test open-ended redlining questions and questions requiring review of redlined documents. This should help to differentiate and more accurately evaluate those vendors who have created specific redlining features designed to handle more complex tasks.

Examples

Q

What changes have been made to the licence agreement and what is the impact of those changes?

A

Indemnity by the Licensor has been added to the agreement at clause 10(b). In terms thereof, the Licensor will indemnify the Licensee and hold them harmless against any claims arising from or relating to (i) third party claims that use of the Licensed Product infringes the intellectual property rights of third parties, (ii) acts or omissions by the Licensors employees that result in any claims, or (iii) breach by the Licensor of any warranties in terms of the agreement or breach of confidentiality / data privacy obligations (as listed in clause 12 of the agreement). The inclusion of Licensor’s indemnity for third party intellectual property infringement at the new clause 10(b) expands the circumstances under which the indemnity may be applicable as it does not limit these claims to those which infringe US IP filings or claims which have a final judgment made or court award.

CORRECT

The response included all expected elements.

In this example, a PDF redline is provided and all participants are asked to identify the changes made and their impact. A single clause was added to the agreement on page 11.

Vincent AI was not able to determine which parts of the document were changed and which parts were from the original—it asked to be provided with the original document and the amended one.

Harvey Assistant had many false positives—flagging items as changes when they were not. However, its long answer did include the one true change in the agreement.

The lawyers, in contrast, easily found the new paragraph and succinctly described its impact.

Again, this is a single sample from a larger corpus and is not reflective how the respondents answered every question.

Transcript analysis

About the task

The Transcript Analysis task was designed to assess the respondent’s ability to review and analyze information and concepts found within a court transcript. The task itself is similar to the Document Q&A task in that questions were asked with respect to a document. However, it focused entirely on transcripts, whereas for Document Q&A we used a wide range of legal documents.

Measuring performance on the Transcript Analysis task is crucial, because court transcripts often contain nuanced arguments and contextual subtleties that require careful analysis. Further, the transcripts are often messily formatted, making it prohibitively challenging for common generative AI tools to be used. Evaluating the ability of these vendors to handle such specialized documents provides insight into their capacity to assist with real-world legal tasks that demand both comprehension and precision.

The Dataset Questions provided by the Consortium Firms required evidence of both practical and legal understanding of the contents of the transcript. The dataset had 30 questions that were asked over six documents. In each sample, there were individual criteria used to measure accuracy. The task had a total of 54 such checks.

Respondents and results

Two vendors opted into this task, so the results show the outputs of Vincent AI and Harvey Assistant, along with the Lawyer Baseline.

Evaluation notes

Both AI tools far surpassed the Lawyer Baseline. Based on these results, lawyers should find value in using generative AI tools to answer questions about transcript documents.

The technical specifications for this task were similar to the Document Q&A task in that the tools were provided with a reference document and asked a single question about it. This similarity is reflected in the finding that both Harvey Assistant and Vincent AI outperformed the Lawyer Baseline.

This task was made more challenging by the format in which the reference documents were structured. The documents were not all composed of “clean,” machine-readable text, but instead were primarily scanned court transcripts. In some cases, multiple pages of transcript appeared on a single page of the scanned document. A high-performing tool would need to read the scanned images into text, tracking page ordering and page-line numbers, while keeping track of the question-asker and the respondent, all across very long documents (often over 900 pages). These challenges in text processing are particularly meaningful for benchmarking AI tools which are regularly expected to handle these types of documents.

The lawyers sometimes failed to piece together related elements of the transcript, identifying part of the relevant context but not always returning the most complete answer possible. The AI tools made mistakes when they did not connect multiple non-continuous sections to form an answer or could not parse out relevant information from the transcript.

Examples

Q

How many lawyers were present to represent Elizabeth? [Reference document: Holmes Transcript July 11, 2017]

A

There were three lawyers representing Elizabeth. Found on pages 2

INCORRECT

The answer states that there were three lawyers representing Elizabeth, while it is expected that there were five lawyers present to represent her. The answer does not specify that these lawyers were from Cooley or provide their names (Stephen Neal, John Dwyer, and Ali Leeper). The expected answer requires information about two specific lawyers from WilmerHale, which is not present.

This is a single example and is not necessarily reflective of the overall performance of the respondents. The findings above and charts indicate that overall performance.

In this example, respondents were asked to confirm how many lawyers present in the transcribed deposition were acting for Elizabeth Holmes, former CEO of Theranos.

Relevant Fragments:

On page 2: 16 On behalf of the Witness : 17 STEPHEN NEAL, ESQ. 18 JOHN DWYER, ESQ. 19 ALEXANDRA LEEPER, ESQ . 20 Cooley LLP

On page 14: 10 MS. CHAN: Do you represent Ms. Holmes in her 11 personal capacity? 12 MR. NEAL: I represent Ms. Holmes in all 13 capacities. 14 MS. CHAN: Okay. And what about Mr . Taylor and 15 the attorneys from Wilmer? 16 MR. TAYLOR: I represent the company Theranos. 17 MR. DAVIES: I represent the company and Ms. 18 Holmes as CEO. 19 MR. MCLUCAS: Same. Company and Ms. Holmes.

This question seems simple but is tricky because on first glance, it appears that page 2 contains all the information required, but in fact, it is essential to read further into the transcript. The first couple of pages indicate that three Cooley lawyers were present to represent Ms. Holmes and two WilmerHale lawyers were present to represent Theranos. However, on page 14 of the transcript, it was clarified that the WilmerHale lawyers also represent Ms. Holmes in her capacity as CEO. Only Vincent AI was able to capture this nuance in its response.

Chronology generation

About the task

The Chronology Generation task was designed to assess the respondent’s ability to identify, describe, and order specified events or facts from a document. The dataset had 10 questions, each asked of a single corresponding document. We measured the quality of generated chronologies with individual “checks” that verify that a date or important fact was included in the response. This task had a total of 118 such checks.

The Chronology Generation task was selected for the study because it represents a critical, time-intensive process frequently required in legal practice. Constructing a precise and comprehensive chronology demands meticulous review of documents to extract, sequence, and organize key events or facts, which can be labor-intensive for human practitioners. This task was included to assess the AI tools’ ability to perform this task efficiently and accurately.

The Dataset Questions provided by the Consortium Firms required the identification of relevant events/facts as specified in the questions and the dates or time periods they occurred within a single document, followed by the presentation of them in an ordered tabular or list format.

Respondents and results

The results show the outputs of CoCounsel, Harvey Assistant, Oliver, and the Lawyer Baseline, as vLex opted out of this task.

Evaluation notes

Producing chronologies is a task that lawyers should see value in using generative AI tools for, particularly to gain time efficiencies. This task required the most lawyer time in producing responses. One of the core challenges in producing high-quality chronologies is judging whether an event or fact is relevant in the first place. This prioritization may be easier for practicing lawyers, explaining why the Lawyer Baseline was set so high at 80.2% (the second-highest baseline score in the study).

While this task was significantly less complex than what might be done in the context of a contentious matter, where key facts might be pulled from a much larger and more diverse corpus of reference documents, the respondents performed well overall.

Both Harvey Assistant and CoCounsel received high scores, with Harvey Assistant matching the Lawyer Baseline of 80.2% and CoCounsel closely following at 78.0%.

The key differentiating factor between all of the evaluated products seemed to be the inclusion or lack of additional detail or explanation of the identified fact/event. Where an additional description was provided, there was typically a better match to the detail required by the reference answer (as is evidenced in the example below).

The level of detail required for a chronology may be subjective, based on lawyer preference or the purpose for which the chronology is being created. Naturally, scores were also negatively impacted where a relevant fact or event was not identified at all.

Performance appeared to decline with increased difficulty and document length. The two highest-difficulty chronologies achieved the two lowest average scores and the three chronologies with the longest reference documents were in the bottom four scores for this task. However, the chronologies with the shortest reference documents did not achieve the top scores, indicating that all respondents can perform well, but not perfectly even with shorter documents.

Ensuring consistency in the required level of detail in answers and providing a breakdown of scoring to differentiate accuracy of the products in identifying the relevant event separately from providing relevant event details may be considered for future studies.

Example

Q

Generate a chronology of the underlying facts of this case and the procedural milestones of the NLRB in reaching its decision (including the date the decision was delivered). The output should consist of a list setting out each key date (month, day and year) with a concise summary of what happened on that date.

A

[omitted]

81.8%

The response failed to identify two key facts.

In this example, respondents were asked to review a decision of the National Labor Relations Board and generate a chronology of the key underlying facts and procedural milestones. Respondents were also asked to provide a concise summary of what happened on each date. The reference answer included 10 relevant facts/milestones.

Although this required the review of a very short, five-page decision, the respondents achieved an average score of 78.2%, with only CoCounsel identifying all of the expected facts and milestones (albeit not as 10 separate events) and all required details about them. Oliver also posted a very strong score of 90.9%, having missed only certain details concerning one milestone.

EDGAR Research

About the task

The EDGAR Research task was designed to assess the respondent’s ability to assist in broad market-based research or answer specific questions relating to U.S. public companies by reference to the SEC’s EDGAR database. The EDGAR Research task was included in the study because Consortium Law Firms expressed interest in exploring this emerging use case for legal technology, recognizing its potential to streamline and enhance market-based research and company-specific inquiries. The dataset had 100 individual questions, with 100 checks for accuracy and 123 checks for citations.

The Dataset Questions provided by the Consortium Firms primarily asked narrow questions requiring specific and concise responses. In some cases, the question identified the relevant filing(s) by name, whereas in others the respondent was responsible for identifying the appropriate filing(s). In all cases, the respondent was expected to provide precise citations for the filings used.

Respondents and results

The results show the performance of Vecflow’s Oliver and the Lawyer Baseline, as all other vendors opted out of this task.

Evaluation notes

Although the SEC’s database of filings is one of the most accessible sources of legal documents, conducting EDGAR Research remains a complicated task. EDGAR Research has been one of the hardest tasks for the AI tools. To do this task, vendors must either conduct a live search of EDGAR documents or maintain their own internal index of the public filings. The challenges with this task were primarily explained by the following:

(1) The questions posed by the Consortium Firms did not typically reference a specific filing type, nor did they include any reference documents by design, meaning the requested searches were very broad and open-ended. The vendors who offer a specific EDGAR search capability sometimes utilize a combination of prompts and filters to help narrow the search scope. The filters will include selecting specific filing types. It is worth noting also that knowing the exact filing type (the names of which are not plainly evident—e.g., an annual report filing for a U.S. company is called a 10-K) requires some specialized knowledge or experience, or otherwise explicit instruction. Without a very detailed prompt, or at least a filing type specified, the search must be done over an extremely large space of documents, compounding the task’s difficulty.

(2) It is unclear if the legal tech products have access to all document types available on EDGAR. Some of the mistakes we saw resulted from a tool’s inability to find information from 497k and N-1 A forms, among others (see the example below). Without having these reference documents, they missed the key information needed to produce an accurate answer.

Unlike the legal tech tools, the lawyer control group was able to use non-AI research tools including Google and the SEC’s own EDGAR search interface to complement their searching. The lawyers had a higher probability of finding the answer, as they had multiple means to do so. It is likely for these reasons that the Lawyer Baseline was set reasonably high and that there is a significant gap between the baseline and the AI tool scores.

These issues with the question formulation and access to a reference database resulted in challenges in computing an accuracy score for each participant. This is discussed in Notes on Study Limitation.

Given the uncertainties in how to complete this task and the need to iteratively access multiple sources of information, EDGAR Research was the one task within our evaluation which could benefit from the use of agentic workflows, that is, workflows in which autonomous AI agents independently make decisions (e.g., which data source to query) and iteratively take series of actions (e.g., search Google to understand the best EDGAR filing type to query, then query EDGAR for that filing type) to achieve their defined goal.

Most notably, Oliver achieved a score of 55.2%, approaching the Lawyer Baseline of 70.1%. They were the only vendor to participate and remain in the task, suggesting the importance of their “agentic workflows” for performing open-ended EDGAR research questions—see the vendors section on Oliver below for more details.

Example

Q

When is the last day that shareholders of the BlackRock Future Tech ETF were able to sell their holdings on NYSE Arca?

A

Shareholders may sell their holdings of the Fund on NYSE Arca until market close on August 12, 2024 and may incur the usual and customary brokerage commissions associated with the sale of Fund shares. At the time the liquidation of the Fund is complete, shares of the Fund will be individually redeemed. If you hold shares of the Fund on August 15, 2024, the Fund will automatically redeem your shares for cash based on the net asset value of the Fund as of the close of business on August 12, 2024, which will include any dividends or distributions calculated as of that date.

Citations:

BlackRock ETF Trust - 497K (June 7, 2024)

CORRECT

The response correctly identified all elements of the reference answer.

In this example, respondents were asked to identify the last possible date on which shareholders of a particular exchange-traded fund (ETF) could sell their holdings on the NYSE Arca trading venue. No other context was provided, requiring respondents to discern that the information was likely contained in the ETF prospectus or a supplement thereto. The respondents would need to know that the ETF in question would have been issued under a fund registration statement of filing type Form 497K, which may be subject to further supplemental filings. ETF prospectuses and supplements are filed under Form 497K.

Clearly, some understanding of ETFs and the related filings, or the ability to search for the necessary information as a first step, would be required to know how to find the answer to this question. Being able to first narrow the search to specific 497K filings would have been helpful. The lawyers were able to correctly find the relevant supplemental prospectus filing and date. Oliver provided a nil return response.

Vendor highlights

CoCounsel by Thomson Reuters

The Thomson Reuters product tested in this study was CoCounsel 2.0, which was released in August 2024 and is now referred to as “CoCounsel.” CoCounsel draws upon a selection of LLMs, including the GPT and Gemini series, and was notable in the study for consistency in its quality of responses.

For the four tasks that CoCounsel opted into—Document Q&A, Document Extraction, Summarization, and Chronology Generation—it received scores ranging from 73.2% to 89.6%. It is the only AI tool other than Harvey Assistant to receive a top score—for the Document Summarization task (77.2%), where it also surpassed the Lawyer Baseline.

Across the four tasks evaluated, CoCounsel achieved an average score of 79.5%. This is the highest average score achieved in the study, although as each vendor opted into a different number of tasks, the overall vendor averages are not comparable. When looking at the average vendor scores for the four tasks that Thomson Reuters opted into for evaluation, CoCounsel has the second-highest-scoring product overall.

Firms and institutions already relying on Thomson Reuters for research and other legal technology tools will see value in adopting CoCounsel as part of the legal workflow. For readers interested in this product, it’s worth noting that CoCounsel Drafting now also provides Word-centric drafting skills separate from the CoCounsel Core set of skills evaluated here. To get the full set of generative AI skills from Thomson Reuters, separate licenses are required for CoCounsel Core, CoCounsel Drafting, Westlaw Precision, and Practical Law Dynamic (together, this package is referred to by Thomson Reuters as CoCounsel 1100).

Vincent AI by VLex

The vLex product tested for the purpose of this study was Vincent AI, which was released in October 2023.

vLex stands out for its comprehensive participation in the study, opting into the second-most number of tasks after Harvey. Those tasks were Document Extraction, Document Q&A, Document Summarization, Redlining, Transcript Analysis, and Legal Research.

For the six tasks that vLex participated in, Vincent AI received scores ranging from 53.6% to 72.7%. Vincent AI performed better than the Lawyer Baseline on Document Q&A, Document Summarization, and Transcript Analysis. The product also gave responses exceptionally quickly as generally one of the fastest products we evaluated.

Vincent AI’s design is particularly noteworthy for its ability to infer the appropriate subskill to execute based on the user’s question, adapting to the user query. In cases where clarification was needed, Vincent AI would proactively ask follow-up questions to refine its understanding, ensuring tailored responses. The answers provided were impressively thorough, often extending beyond two pages, which may prove especially beneficial for junior lawyers, offering valuable additional context to aid their understanding and workflow. When the legal research database did not have sufficient data to answer a question, Vincent AI refused to answer, rather than hallucinate an illegitimate response. Although this negatively affected the vLex scores, it is better for an AI tool to recognize its limitations.

Although our evaluation focused on a small slice of Vincent AI’s capabilities in the U.S. jurisdictions, its support for international matters is a significant strength. For global law firms, this capability may provide a level of utility unmatched by other tools, making Vincent AI an attractive choice.

Harvey Assistant by Harvey

Harvey’s platform leverages models to provide high-quality, reliable assistance for legal professionals. Harvey draws upon multiple LLMs and other models, including custom fine-tuned models trained on legal processes and data in partnership with OpenAI, with each query of the system involving between 30 and 1,500 model calls.

Harvey opted into more tasks than any other vendor: Document Q&A, Document Extraction, Document Summarization, Redlining, Transcript Analysis, and Chronology Generation. Harvey was the top-scoring product in five tasks (Document Q&A, Document Extraction, Redlining, Transcript Analysis, and Chronology Generation) and surpassed the Lawyer Baseline in all but Redlining. Harvey also had the highest score of any respondent in any one task, achieving a 94.8% for Document Q&A, and received two of the top three scores awarded overall. This makes Harvey Assistant the strongest-performing product in this study.

Firms and institutions will see value in adopting Harvey. In addition to the features for which Harvey Assistant was evaluated in this study, Harvey offers a full drafting suite, including a Word Add-in, which does not require an additional license. Harvey also offers Document Extraction at scale in its Vault product, and a growing number of agentic workflows to support lawyers in undertaking end-to-end workflows without requiring detailed prompting.

Oliver by Vecflow

The Vecflow product tested for the purpose of this study was Oliver, which was released in September 2024. Oliver draws upon Meta’s Llama models, as well as Open AI’s o1 and Anthropic’s Claude 3.5 Sonnet.

For the six tasks that Vecflow opted into—Data Extraction, Document Q&A, Document Summarization, Chronology Generation, and EDGAR Research—it received scores ranging from 55.2% (for EDGAR Research, for which it was the best-performing AI tool) to 74.0%. Oliver bested at least one other product for every task it opted into. Oliver also outperformed the Lawyer Baseline for Document Q&A and Document Summarization. Although it did not exceed the Lawyer Baseline, Oliver was still the best-performing, and only, product in answering the EDGAR Research questions.

Vecflow is the youngest company included in this study, yet their product, Oliver, often performed on par with or outperformed more established offerings. In the challenging EDGAR research task, Oliver, through its coordination of specialized AI agents, stood out as the sole offering capable of nearing human-level performance.

Leveraging an agentic workflow, Oliver not only processes legal tasks efficiently but also excels at explaining its reasoning and actions as it works, making it particularly user-friendly. This capability is a key differentiator, empowering legal professionals to trust and understand the AI’s outputs in real time. We suspect that Oliver’s superior performance on EDGAR Research tasks, which provided less specific instructions and demanded multi-step reasoning and iterative decision-making, was due to its advanced use of agentic workflows. Oliver’s success highlights Vecflow’s potential to innovate in legal tech.

We can only expect Oliver to advance further over the course of the next year. Lawyers looking to engage with a rapidly growing startup may consider piloting Vecflow’s offering. Additional Findings

Additional findings

Latency

Overview

In addition to the accuracy of the tools, we measured the speed with which models could return a response (latency). We measured the total time to return a response, starting as soon as the file upload is initiated, and completing when every token is returned. In the results below, we average the response time across the tasks for which all vendors participated.

| Lawyer Baseline | CoCounsel | Vincent AI | Harvey | Oliver | | --------------- | --------- | ---------- | ------ | ------ | | 2326s (38:36) | 41.8s | 34.5s | 28.6s | 365.8s |

We found that the Harvey Assistant is consistently the fastest, with CoCounsel also being extraordinarily quick, both with sub-minute average response times. Oliver is the slowest, often taking five minutes or more per query, likely due to its agentic workflow, which breaks tasks into multiple steps. This process runs in the background and can potentially improve reliability and thoroughness, despite the longer overall run time.

While there were differences in response time from the AI tools, they were all still exponentially faster than the lawyer control group. The AI tools were six times faster than the lawyers at the lowest end, and 80 times faster at the highest end. For this reason alone, it is important to consider these tools as categorically different. The generative AI-based systems provide answers so quickly that they can be useful starting points for lawyers to begin their work more efficiently.

Notes

All measurements include file upload time. Files were not reused, meaning even if the same file was used in multiple questions, we re-uploaded it every time.

Although, in general, all data was collected and submitted by the same server, there may be fluctuations in response time based on factors like time of day. All tests were run outside of standard work hours and therefore represent a lower bound on the speed expected.

For Vincent AI, an API was not provided, so the responses had to be collected by hand, meaning that it also needed to be manually timed, likely leading to more variation.

Response length

For some skills, we noticed a correlation between response length and accuracy. This may be because more verbose tools having a higher chance of including elements expected of an ideal response. We wanted to highlight this difference in response type as an attribute law firms may choose to evaluate on a case-by-case basis—some lawyers may benefit from more verbose explanations while others may want a quick answer to begin their work.

In general, we found that Oliver had the most verbose responses, making sure to provide an explanation for how each answer was produced. The lawyers tended to respond most tersely, giving the minimum possible answer for a question. This could be due to the lack of specific context (e.g., document audience, purpose, risk profile, etc.) that a lawyer would ordinarily have when responding to these sorts of requests. CoCounsel generally did well in balancing both high accuracy and medium response length.

Future plans

This study represents the first iteration in what will be a regular evaluation of legal industry AI tools. It is critical for legal buyers to understand whether products are able to perform at the levels advertised, particularly when the startup landscape is evolving rapidly. Providing regular benchmarks will show the progress of existing vendors as well as scores for new products. Having established benchmarks and a trusted methodology, we intend to continue to use these to improve transparency in legal AI. As such, our plans for the future of this study involve expansion in various areas.

New vendors

As we shared above, a number of additional legal AI vendors have already approached the study organizers asking to be included in the next round of evaluation. As new (relevant) vendors opt in to benchmarking their solutions, and buyers seek an evaluation of startup offerings that elect to participate, we will incorporate those products in future rounds of the study.

New skills

Just as vendor interest in benchmarking increases, we anticipate that buyer interest in expanding the purview of the study will also grow. This interest is likely to be compounded by additional capabilities developed by legal AI tools. The scope of the current study was necessarily limited by resources and interest areas at Consortium Firms, tasks covered by participating vendors, and the capabilities of legal AI tools at the time of writing. As new firms join the Consortium and the arena of legal AI products evolves, we anticipate that new task areas and skills will be added to future study iterations. As a corollary to this, we expect to continue to build out the dataset for evaluation, both to bolster current benchmarking areas and to accommodate expansion into new ones.

Expanded Jurisdictional Coverage

As an initial foray into AI product benchmarking, this study has been focused exclusively on the United States, meaning that the dataset and skills evaluated are specifically applicable to the practice of law in U.S. jurisdictions. As part of our collaboration with the U.K.-based Litig AI Benchmarking initiative, we eventually plan to expand the scope of further studies to cover first the U.K. and subsequently other international jurisdiction datasets and skills. This will allow for more global relevance and will ensure that the transparency and trustworthiness gains provided by the VLAIR can be accessed by a broader population.

As vendors with dominant customer bases outside of the U.S. seek to participate, study organizers will approach law firms and buyers in relevant markets for generation of datasets that allow for jurisdictional expansion.

Additional Support

As the study progresses and iterates, it will require participation by additional industry players. The philosophy underpinning this study is that trustworthy research into legal AI efficacy requires support and active involvement by all members of the legal community. The Dataset Questions and benchmarks summarized in this report can be relied upon because they represent real work undertaken by lawyers, as vetted by the law firms who are buyers of the products evaluated.

In future iterations of the study, we hope to draw upon expertise and support from more law firms, especially as we expand the study into new jurisdictions, and ultimately as well from corporate legal teams who similarly represent buyers in the market. If you are interested in contributing to a future iteration of the study, please get in touch by emailing contact@vals.ai.

As previously mentioned, we expect to expand the study to include new vendors and legal tech tools in subsequent iterations. If you would like to see your product or another company’s product on the market benchmarked, again get in touch with contact@vals.ai.

Notes on study limitation

This study represents an ambitious industry-first effort to evaluate the most popular legal tech vendors on data sourced by the top global law firms. Even still, our methodology includes key limitations worth noting. We expect to continue improving our methodology, overcoming limitations with each iteration.

EDGAR Research

For the EDGAR Research task, the tools were prompted with a question alone. Our methodology did not allow for the nuance of applying a filter for the type of documents to be included in the search. Moreover, the way the questions were written was not optimized for the AI tools included in the study. This is not necessarily how the products were designed or how lawyers expect to use these products. Future iterations of the study may seek to change how the questions are framed (to include more context that helps to narrow the search), or a filter for filing type is provided alongside the question.

In addition, the reference answer citations provided by the Consortium Firms and the response citations provided by the lawyers primarily comprised links to the relevant online filings, whereas the AI tools produced either or both links and textual citations. When conducting the check of citations for this task against the reference answer citations, an inordinate number of failures were produced. When these failures were reviewed, we found that the same filing may be accessed through multiple URLs. To remedy this, a citation score was produced by extracting the title and date of the filing at each response link provided and comparing this to the title and date extracted from the reference answer citation.

However, we also found there were often multiple valid document names that could be cited. For example, a prospectus forms part of a registration statement and can be accessed separately or as part of the registration statement. This made it difficult to automatically assess the correctness of the citations provided without a complete human review. As this issue arose towards the end of the evaluation process, it was not possible to secure additional resources to manually check each citation. Therefore, we chose to separate out the citation score from the accuracy score, so as not to prejudice the overall scores for the skill.

While these initial findings are useful, we will revisit the design of this task, including both the formulation of the research questions and the methodology for checking EDGAR citations, in order to ensure we can successfully evaluate this task in future iterations.

Larger corpora